Sunday School

The Chronology of the New Testament, part four : What About Q?

Welcome back to Sunday School! Class is officially in session. You may want to buckle up for this one, because we are going to take a deep dive into some glorious Bible nerdery. This week we are going to pause our chronological journey through the New Testament (NT) documents to respond to a reader question. This isn’t a tangent, however. It’s a question that fits nicely into where we are chronologically in the development of the NT materials (last time we talked about the Gospel of Mark, written in 70 CE).

Darryl asked,

“What is your opinion on the Q reference source for the Gospels?”

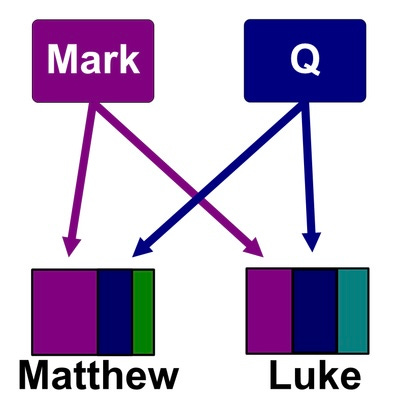

This is such a good question! When we talk about Q we are also talking about something called the Synoptic Problem. Due to their similarities the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, and Luke are known as the Synoptics.1 Matthew and Luke clearly have incorporated significant portions of Mark into their accounts. Those two Gospels also seem to contain content that is independent of one another, sources usually referred to as M and L respectively. However, there is also a good bit of content that is shared by Matthew and Luke, but is not found in Mark. How do we explain that overlapping material, present in Matthew and Luke, but absent from Mark? That is a brief sketch of the Synoptic problem.

By 1900 scholars had reached a general, but not universal, consensus that the best explanation for that shared material that is in Matthew and Luke, but not in Mark, was something called Q. The letter “Q” is shorthand for Quelle, which is the German word for “source.” The idea behind this hypothesis—and it is still a hypothesis, meaning proof has never been found—is that Matthew and Luke both, independently, had access to the same source, Q. Each author incorporated material from Q into their Gospel accounts, without being aware the other was doing such, and that explains the Synoptic Problem.

Scholars who affirm this perspective see Q as a text that is earlier than any of the Gospels we have. It’s usually dated in the 50s CE, twenty or so years after Jesus and contemporary with the authentic letters of Paul. There are some who argue that Q is even a layered tradition, with perhaps three different stages of development spanning the 50s - 60s CE. However, that has never been a widely accepted view.

Q is different from what we think of as a Gospel in that it is not narrative based. It’s not focused on telling stories of Jesus, but is primarily a collection of sayings attributed to Jesus (and John the Baptist). As a result few familiar stories appear. It also is not focused on what many see as the central events of the Christian story —there are no accounts in Q of Jesus’s birth, death, or resurrection. There is also only one account of any miraculous work of Jesus, although that Jesus worked wonders and performed exorcisms is remembered in the sayings.

There are variations on the theory, like the Two-Source (Mark + Q) or the Four-Source (Mark + Q + M/L), but all the main theories prioritize Mark as the first Gospel, used as a source by Matthew and Luke, who also each, independently, has access to a sayings source, Q.

A great little introduction to Q can be found in a book edited by the late, great Marcus Borg called, “The Lost Gospel Q: The Original Sayings of Jesus.”

Now that we have a general overview, back to Darryl’s question. What do I think about Q? For the past twenty-some years, since learning about Q in college, I have accepted it as the best explanation for the Synoptic problem. Like a growing number of others, that has begun to shift for me in recent years. That shift is not because of Q’s hypothetical nature. It doesn’t seem that far-fetched to me that a collection of sayings, some of them even things actually said by the historical Jesus, would exist. If anything the discovery of the Gospel of Thomas at Nag Hammadi, Egypt in December 1945 lends more credibility to the idea. While most scholars date Thomas in the second century or later, it is a Sayings Gospel, comprised not of narrative, but of words attributed to Jesus. It’s not the hypothetical nature of it that caused a shift for me.

To put it simply, something like Q might have, or even probably, existed it just isn’t necessary to explain the Synoptic Problem. Here’s what I mean: a growing number of scholars have started to revise their dating of Luke’s Gospel, moving it from the late 80s to perhaps as late as the 110s CE. For reasons I’ll share later in this series, that change in dating makes sense to me.

That being the case, here’s how I would describe the literary relationships between the Synoptic Gospels:

Mark wrote first, around the year 70 CE.

A decade-ish later, in the 80s, Matthew wrote, using Mark and whatever other sources he had available.

Finally, as many as thirty or more years later, Luke wrote using Mark, Matthew, and his own sources.

This is often called the Farrer Hypothesis, named for English scholar Austin Farrer, who wrote challenging the idea of Q in the 1950s.

The TLDR of this is that I’m not “anti Q.” I just don’t see Q as necessary to explain the Synoptic problem. It is far more simple to see Luke as having access to Matthew’s Gospel, in addition to Mark and his other sources.

Whew. What a ride! I hope this dive into Bible nerdery has been as fun for you as it was for me! Let me know what you think in the comments or chat, and always feel free to leave your questions and curiosities. Thanks so much to my reader and friend Darryl for the great question!

From the Greek word συνοπτικός/synoptikos, which means “seeing together”.

I was introduced to Q in my New Testament class at WKU. Dr. Lane was my instructor and her was a scholar on the gospel of Mark. This was the beginning of my search for more than what I knew from my traditional Sunday School and Training Union. I am still searching.